Unholy Terror: The Psychological Grip of Religious Horror on Audiences

- Ghita Sadik

- Oct 12, 2024

- 4 min read

Religious horror occupies a deeply unsettling corner of the genre, where fear isn’t just

about monsters, ghosts, or killers, but something far more insidious—the questioning of faith, the unraveling of spiritual safety, and the terrifying idea that divine forces might not always be benevolent. This genre exploits the fear of the unknown, of the afterlife, of sin and redemption, creating a complex web of spiritual dread. The connection between religion and horror is potent because both deal with the unseen and the ineffable. The psychological impact of religious horror lies in the way it blurs the line between what is sacred and what is monstrous, a theme masterfully illustrated through films, books, and television series that use religious symbols and narratives to unnerve and provoke.

In The Omen series, religious prophecy becomes a ticking time bomb. The film taps into the Book of Revelation, a text filled with visions of apocalyptic destruction and the rise of the Antichrist. The child Damien, marked with the infamous “666” birthmark, is not just a symbol of evil but a manifestation of divine prophecy. The horror comes not from the idea that this child is evil, but that his existence is predestined—written into scripture long before the events of the film unfold. The inevitability of his rise to power is what terrifies, as characters attempt to intervene only to be thwarted by the invisible hand of fate. The use of religious artifacts, like the daggers of Megiddo, adds another layer to this terror. These sacred weapons, meant to kill Damien, remind the audience that religion is both a source of salvation and a tool of destruction. Their failure, despite their holiness, casts doubt on the protective power of faith.

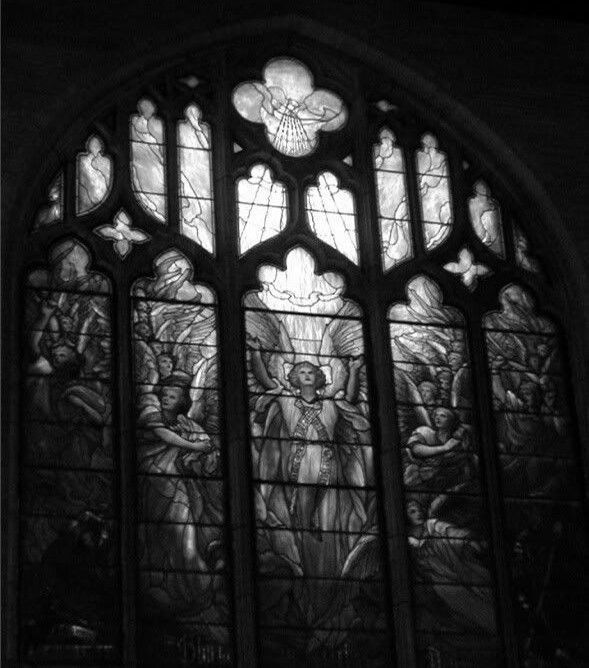

Religious horror often works because it takes the familiar and turns it into something nightmarish. In the ongoing show Grotesquerie, angels—typically depicted as benevolent, protective beings—are transformed into instruments of divine wrath. Their presence is not reassuring but terrifying; they come not to save, but to judge and punish. This inversion of the sacred is deeply unsettling because it preys on the idea that divinity might not always align with human morality. One of the show’s most haunting moments occurs when an angel, wielding a sword of light, descends upon a village not to protect but to eradicate sin in a brutal, indiscriminate slaughter. The sword, often a symbol of justice or defense, becomes a weapon of terror in this context, forcing viewers to reconsider the line between justice and cruelty.

This theme of divine forces acting beyond human understanding is also present in Immaculate, a film that explores the horror of immaculate conception—an event traditionally seen as a miracle, reimagined here as a curse. The young woman chosen to carry this “divine” child is stripped of agency, her body and life offered up to a higher power with little concern for her own will or safety. The religious iconography throughout the film—blood-stained altars, ritualistic chants—creates a claustrophobic atmosphere, where even prayer becomes a form of violence. The psychological horror comes from the perversion of something holy; the act of conception, meant to bring salvation, becomes a mechanism for control and terror.

Gothic literature, too, has long used religion as both a backdrop and a source of horror. In Matthew Lewis’s The Monk, the protagonist’s descent into sin is marked by a series of increasingly blasphemous acts. Here, religious symbols like the cross and the rosary are not sources of salvation but reminders of the monk’s hypocrisy and moral degradation. The church, which should be a sanctuary, becomes a place of secrets, guilt, and corruption. The Gothic mode often presents religion as something to be feared, where the threat is not just physical but spiritual. The novel’s depiction of holy relics as objects of temptation and sin rather than piety adds to the psychological terror, as the boundaries between the sacred and the profane collapse.

One of the most potent aspects of religious horror is the way it forces the audience to confront the unknown. It taps into the existential fear of what lies beyond death, and whether divine forces—if they exist—are benevolent, indifferent, or even malevolent. This is evident in films like The Exorcist and The Omen, where characters seek out religious solutions to fight evil, only to find that the line between salvation and damnation is far thinner than they’d imagined. The sense that faith might not protect, that rituals might fail, is terrifying because it undermines the very foundation of spiritual belief.

Moreover, religious horror often deals with the concept of divine punishment. In both The Omen and Grotesquerie, characters are not simply facing external evil but the possibility that they are being judged for their sins. This is perhaps one of the most psychologically impactful elements of religious horror: the fear that one’s own moral failings may bring about divine retribution. In The Omen, the deaths of those trying to stop Damien are not random—they are framed as punishments, inflicted by a higher power. The priest impaled by a lightning rod, the decapitated photographer—these deaths echo the idea of cosmic justice, a terrifying reminder that human lives are subject to forces beyond our control.

Religious horror plays on deep psychological fears—fear of the unknown, fear of divine judgment, and fear of losing control over one’s fate. It turns faith into something frightening, blurring the line between salvation and damnation; thrives on the unsettling idea that what we hold sacred can be terrifyingly corrupted, forcing us to question the very foundations of faith and morality. By using symbols like the cross, the rosary, the Bible, and even angels themselves, these stories unsettle audiences by taking the very things that are meant to provide comfort and protection and twisting them into instruments of fear. Whether through the predestined rise of the Antichrist, the terrifying power of divine beings, or the perversion of sacred rituals, religious horror forces us to confront the terrifying possibility that the divine may not be on our side.

Comments